Theatre Design in the Time of COVID-19

Theatres closed again in 1918 for the Spanish Flu, and again in 2003 for SARS. COVID-19 isn’t the first pandemic that the theatre world has lived through. Theatres will open again. When? It’s hard to say, but when they do, they will bounce back as they have before.

The return of live events in the transition following a pandemic can captivate and send a strong message. To mark the end of SARS, the Canadian government put on a free outdoor concert at Downsview Park in Toronto. It was both a party and way to say that the SARS outbreak was over, and signal to the rest of the world that Canada was open. I have no doubt that theatre will come back to do exactly that when it does.

The most exciting thing to think about is the way architecture will interact with theatre form in smaller ways.

Art has already changed as a result of the way we are communicating in this pandemic. More people are becoming well versed in putting their art online and collaborating online. We have seen the birth of another art form.

For instance, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s recording of Appalachian Spring from home; they were among the first companies to do this, and the choice of music was particularly inspiring.

These online live shows connect audiences with the musicians through familiarity. It brings the viewer closer to each individual musician – seeing them in a way that is recognizable and relatable (similar clothes, headphones etc.).

Are we going to miss that?

I’m very curious how artists will engage their audience when theatre and performance returns. Will there be more connection through watching musicians via phone, tablet etc? Will there be more openness to live recordings?

Those barriers started to come down when the media first started to come out with “lives” – however, there has been a sea-change in attitude.

Will there be connection from theatre to theatre?

Will there be connection stage to backstage?

Will there be connection from audience to backstage?

I hope the use of those technologies that got us through this time and brought us closer together out of necessity will continue.

People in Italy are opening up their balconies to connect to each other – transforming outdoor spaces into little stages. I think this is an amazing concept for dramatic device. The isolation imposed by this pandemic is ironically dissolving barriers to performance. You can’t repress the human desire to create and express.

We experience this kind of Juliet balcony performance as something spontaneous, heartfelt, the result of a desire to connect – and this, too, will be of service to theatre.

Another observation is the way things are being staged. For example, the clapping and banging of pots for healthcare workers, and singing into the streets – will that cross the proscenium in live theatres, will there be a hunger for that kind of spontaneity? Will the architecture inflect to make that happen? Design can address the kind of connection we seek in a live performance. For the re-imagined David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, we are eliminating the formality of the proscenium to create a more engaging experience.

If I were a set designer or writer, I would want to incorporate these elements and connect physically through the stage, connect the audience to the stage, have actors bring these devices to the foreground because we have all lived through this, and experienced these performances.

Will we also see a continuation of these little stages as we begin to open back up?

I can’t help but think of the porch festivals that happen in neighbourhoods in Montreal and Toronto, where grassroots concert series take place on people’s front lawns. You could have a series of smaller performances with the audience two metres apart on the sidewalks and streets. We could take that idea further, to utilize the outdoor spaces we’ve built into our performing arts venues, such as the plaza at Buddy Holly Hall in Lubbock, Texas, or the Place des Arts at Montreal’s La Maison Symphonique. We could start to have smaller outdoor performances in a transition back to indoors.

It’s hard to see how we could open a traditional theatre with social distancing restrictions, unless we are clever about it.

Let’s take a look at how we could apply “house-bubbling” to block sections out in a theatre – and sell a show that way.

The idea of ‘double household’ or ‘double family’ bubbles is already being talked about as a phase in easing social distancing. We are seeing this in a few provinces here already. What does it look like to see what groups of people two metres apart?

There is some historical precedent to this idea; in old opera house the boxes were family owned. I could see that coming back with housing bubbles. Everyone has their own seat, and each group has their own timed intervals of when to arrive. And then everyone is there and hyper conscious of the different groups around them. Who cheers loudest? Who laughs the most? I could see that being pretty fun.

For this to realistically work, one would have to ensure, at the very least:

a) the air supply and return did not draw air across rows (this is true in theory for displacement ventilation).

b) the actors and production crews were in bubbles and could rehearse and work safely.

c) the audience entering and exiting could be staggered.

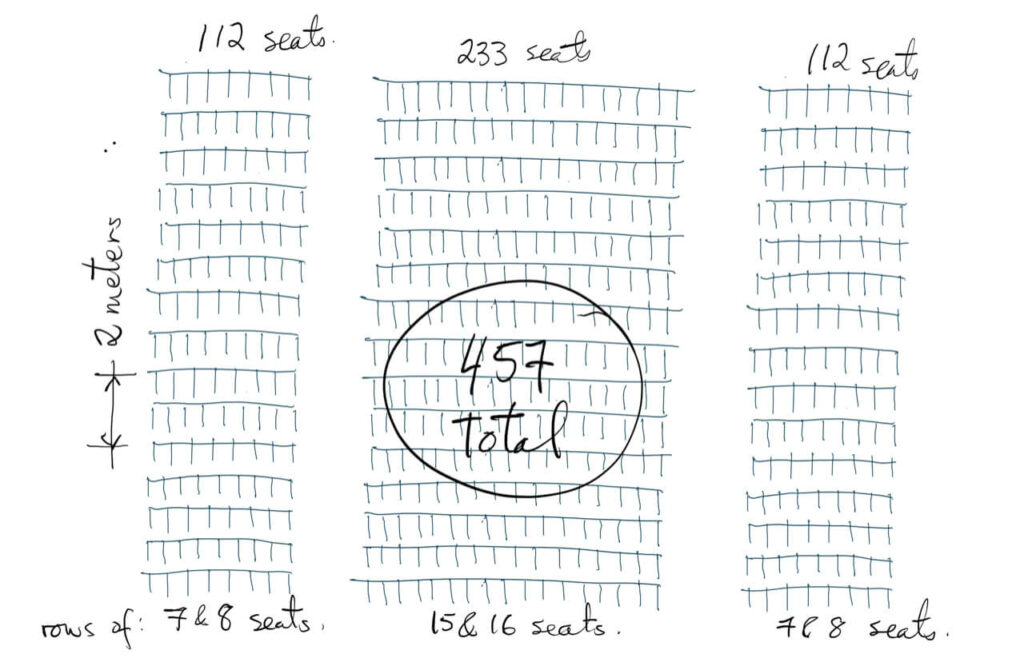

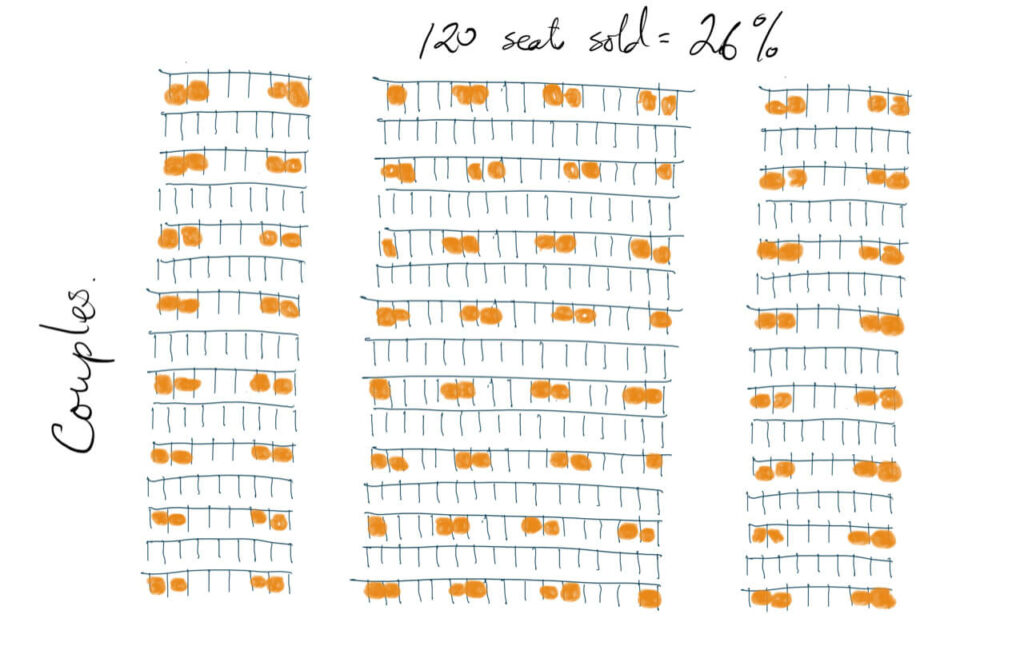

Below is a diagram of a typical orchestra level floor with a centre section and two aisles. We often lay these out with alternating rows of 7 and 8 for the side sections and 15 and 16 for the centre section. (This layout combines typical code restrictions and sight line requirements). A usual row-to-row distance is between 36-39 inches, so for simplicity, I’ve assumed one metre. I’ve also assumed the aisles allow for two metre width.

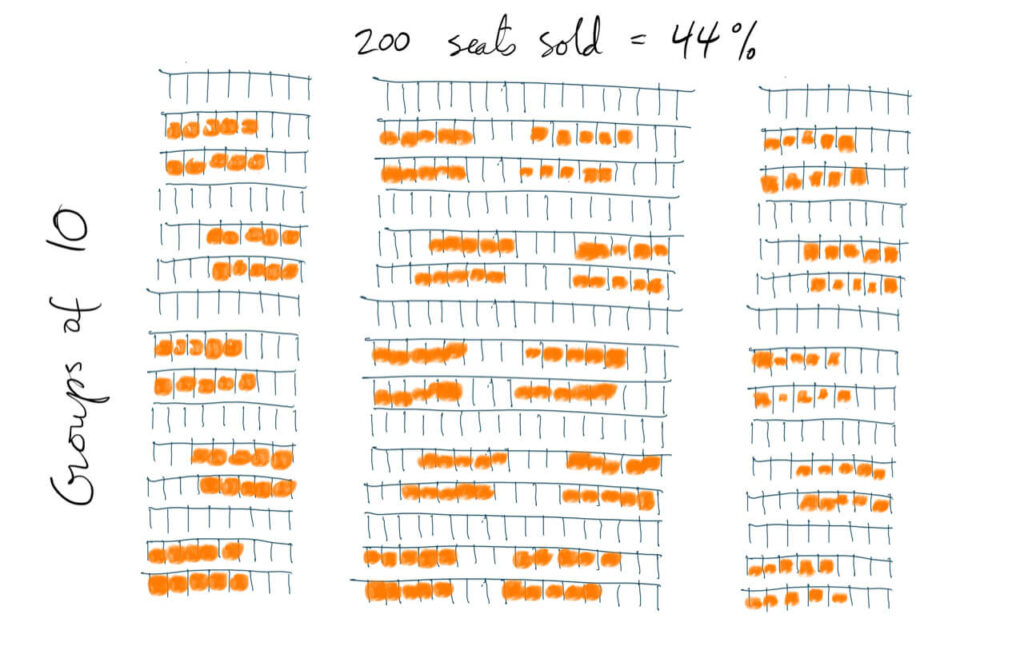

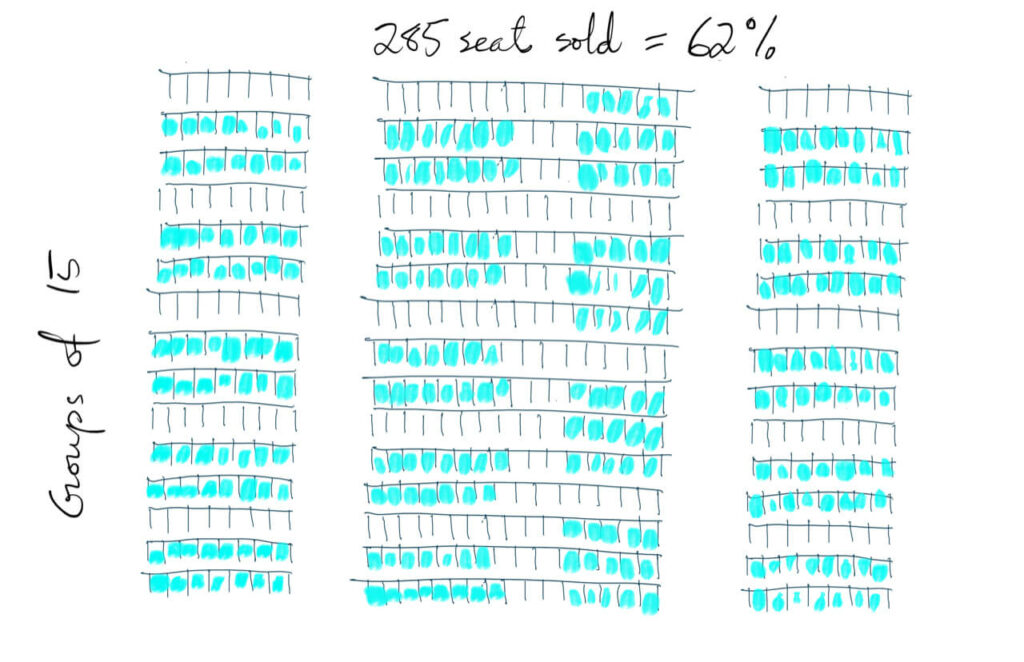

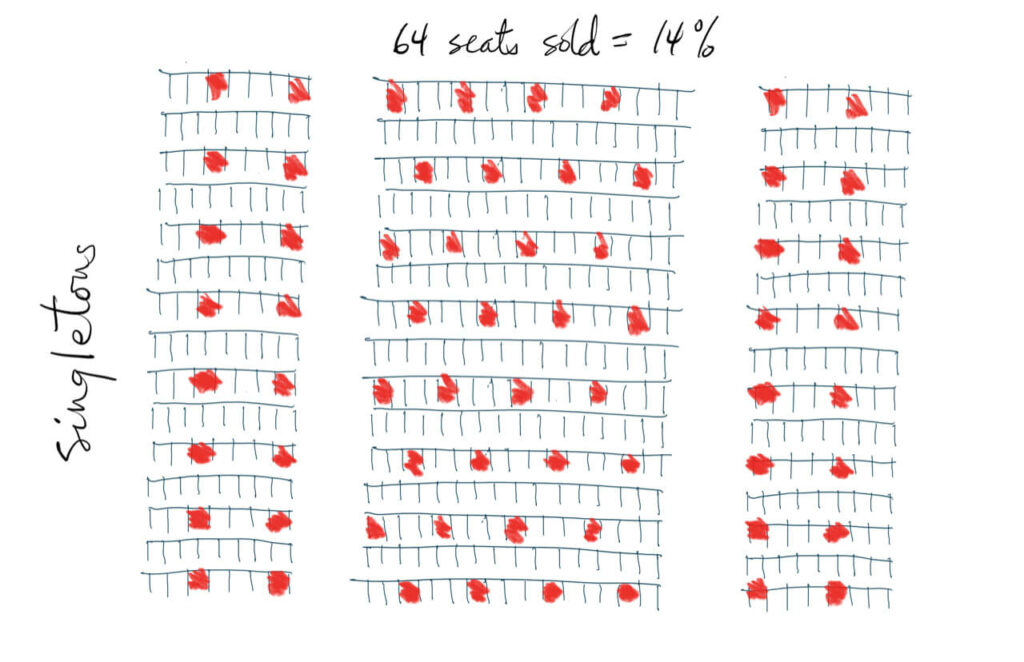

The next diagrams show what happens if you try and lay out bubbled groups of different sizes, keeping people who are not in the same bubble a minimum of 2m apart.

What’s interesting to me is the idea of ‘double household’ or ‘double family’ bubbles. If a theatre could sell tickets in clusters of 10 (one double household) then the house starts to feel a little more legitimately full.