Globe and Mail Op-Ed: Health and Wellness at Ontario Place

For more information, please contact:

Don Schmitt, Principal

Email: [email protected]

Gary McCluskie, Principal

Email: [email protected]

As the architects behind Therme’s Ontario Place project, we feel the park’s revitalization is key to Toronto’s future

Written by principals Donald Schmitt and Gary McCluskie who are leading the design of Therme’s Ontario Place project.

The shouting matches over the new plans for Ontario Place have created so much heat, it’s hard to see the light anymore.

But creativity matters, great design matters, and a high standard for public parks and public buildings matters. Most of all, facts matter. You can build great cities on them.

So let’s start with the facts. The islands of Ontario Place opened more than 50 years ago, in 1971. As a park in the heart of the city, it was, for the first half of its life, a jewel. But it closed in 2012, a directionless victim of infrastructure allowed to deteriorate.

Meanwhile, Toronto spent those same five decades blooming into a metropolis of more than six million people. It is a city with a remarkably diverse population; more than half of its residents identify as a visible minority. Yet we also face shortfalls in housing, public and social infrastructure, and the consequences on our health are clear. Research by the London School of Economics shows the lifespan in poorly served east London is seven years shorter than well-served west London. Depression, meanwhile, affects one-quarter of a billion people, and the World Health Organization identifies that non-communicable diseases, such as respiratory and heart diseases, kill 41 million people a year; these can all be mitigated by a focus on exercise, wellness and recreation.

These sad and startling statistics force us to ask some urgent questions about the places where so many of us live. How do we design cities to be more equitable? How do we plan to ensure that residents of the metropolis experience a greater degree of well-being? One answer is through enhancing social infrastructure – parks, places for community, and places for well-being – and that is precisely where Ontario Place can make a difference.

Eleven years ago, after Ontario Place was closed, the provincial government created a seven-person panel, chaired by John Tory, to consider its future. The panel made 18 recommendations, most of which have shaped the current plan for Ontario Place.

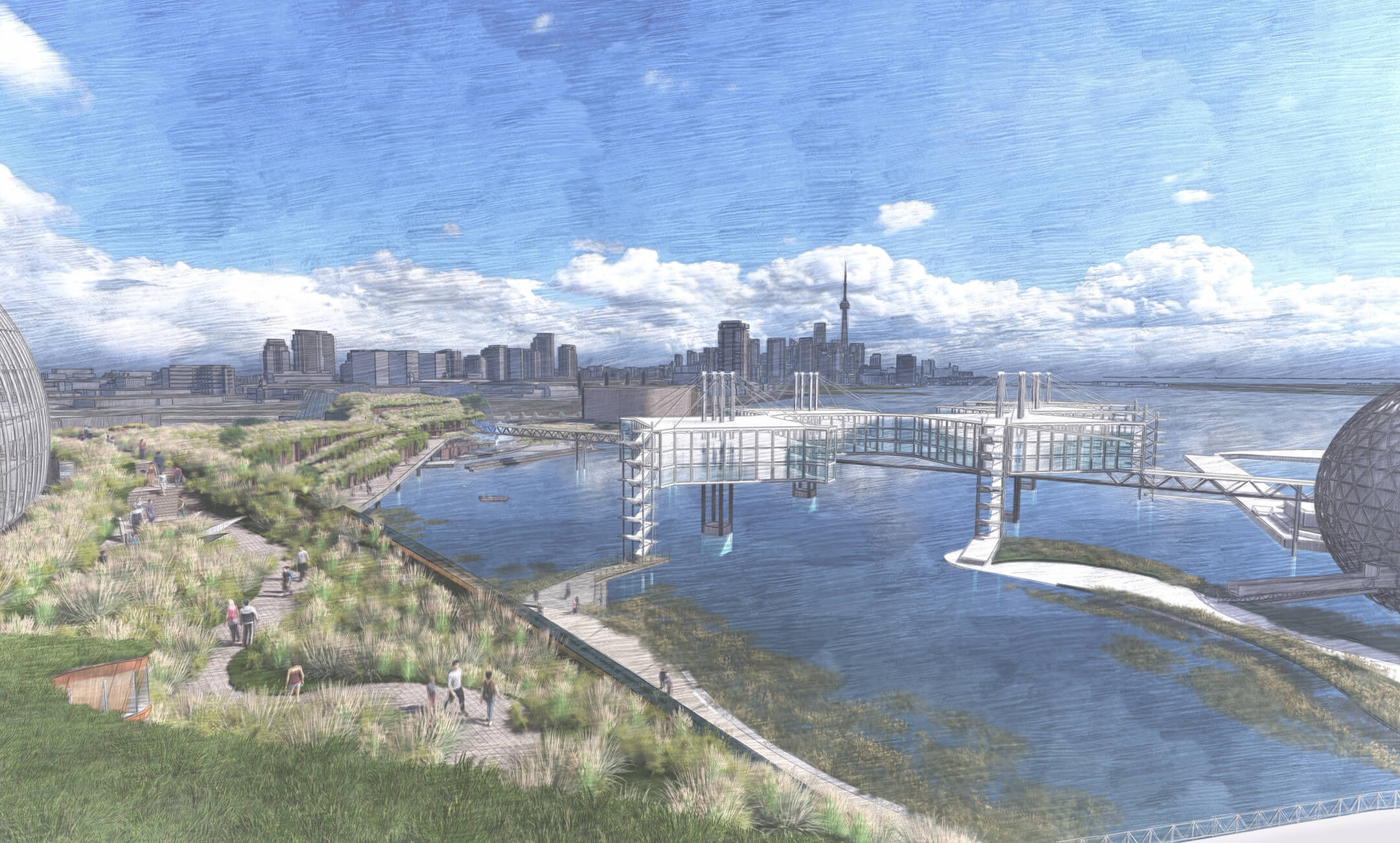

The first initiative to emerge from that plan was Trillium Park, designed by West 8 and opened in 2017. The 7.5-acres of formerly derelict shoreline accounts for 10 per cent of Ontario Place’s 79 acres of land, and fronts the city to the east. It was designed with the participation of members of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, producing beautiful, public green space. Its only shortcoming is the lack of water access for people – something that was intended, but was ultimately cut from the plan.

The second initiative, a 40-acre publicly accessible park space, is in the works; it will be designed by Martha Schwartz, the distinguished American landscape architect.

The third includes 12 acres of green park, designed by Studio tla and built by the Austria-based global wellness organization Therme, which will transform half of the West Island and include a continuous public lake-edge promenade, a new public beach equal in size to Sunnyside Beach, and a new protective headland to halt the shoreline degradation and erosion that has occurred over the last five decades.

In total, between the three landscapes, nearly 60 acres of the original 79 acres of land that comprise Ontario Place will be green park that is free and completely publicly accessible. It will be the second-largest public park in Toronto, and one-and-a-half times larger than Trinity Bellwoods Park, which ranks third.

Still, despite this significant public park space being delivered, this is not enough. Toronto as a metropolis urgently needs a social infrastructure of health and well-being – and that includes a place that promotes collective well-being year-round, even through the cold and windy winters. Therme’s well-being destination will create an indoor option so that Ontario Place can be active 365 days a year.

There have been protests to that plan, however, and they beg some urgent questions.

Is public recreational space defined only as grass and trees? Could a recreational and therapeutic warm-water environment for an estimated 7,000 people a day actually be seen as a social respite in Toronto’s months of windy and winter weather?

Is it reasonable, as with most privately operated indoor cultural, sports and recreational environments, that a daily fee is charged? (In the case of Therme, it is $40 per day.)

Can social infrastructure play a role in civic life? The distinguished architectural critic Paul Goldberger certainly thought so, when he spoke at the Therme-sponsored Wellbeing Leadership Summit last month and described Therme facilities in Europe as the “most democratic space I’ve ever encountered.”

How important is infrastructure that’s focused on health and wellness for thousands of daily visitors, when the Ontario government spends almost 40 per cent of its budget on health care, yet our society spends a fraction of that on preventative care? Can architecture that aims to weave landscape, therapeutic space and recreation together within a public park create much-needed community space?

Can a naturally ventilated, LEED Platinum-certified community facility strengthen the long-term environmental resilience of the city? Does occupying 13 per cent of the total acreage of Ontario Place, as Therme does, overwhelm the park, as some critics allege? Is 13 per cent of a park too much for late-fall, winter and early-spring recreation? When is a public building too tall? With heights that are predominantly one-third lower than Frank Gehry’s glass-enclosed, privately funded Louis Vuitton Foundation Museum in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne public park, does Therme qualify?

Does a new piece of social infrastructure, privately funded and built on public land, threaten public finances, particularly when an annual annuity is delivered to the taxpayer through the 95-year lease the company signed with the province? Was it appropriate, say, that the affordable and market housing projects in the West Donlands were built on public lands leased to developers for 99 years?

When is public consultation adequate? More than 9,500 people have commented on the project in person or online in the last three years. Has the city-planning review, which has followed the same process and protocol as any other public or private project, been flawed?

And can the communities in financially constrained cities benefit when hundreds of millions of private dollars are being offered for investment into physical and social infrastructure? To be clear, no public funding is allocated to Therme or any part of the West Island park, beach, public bridges and shoreline walkways, infrastructure, or the wellness destination. Capital funds for restoration of heritage and infrastructure on the rest of Ontario Place and a future garage are being made by the province.

The repair and revitalization of Ontario Place is critical to Toronto’s future. The inclusion of social infrastructure as a critical place of wellness and recreation represents an enormous opportunity to innovate and transcend. It’s time to see the light.

Read the Op-Ed in The Globe and Mail here.