Night at the Museum (Station)

Museum Station was re-imagined based on artifacts from the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) and the Gardiner Museum, which are directly above the station. Part of the Toronto Community Foundation’s “Arts on Track” initiative, the design reflects the commitment of the Foundation to the idea of beautifying and invigorating public spaces in the city.

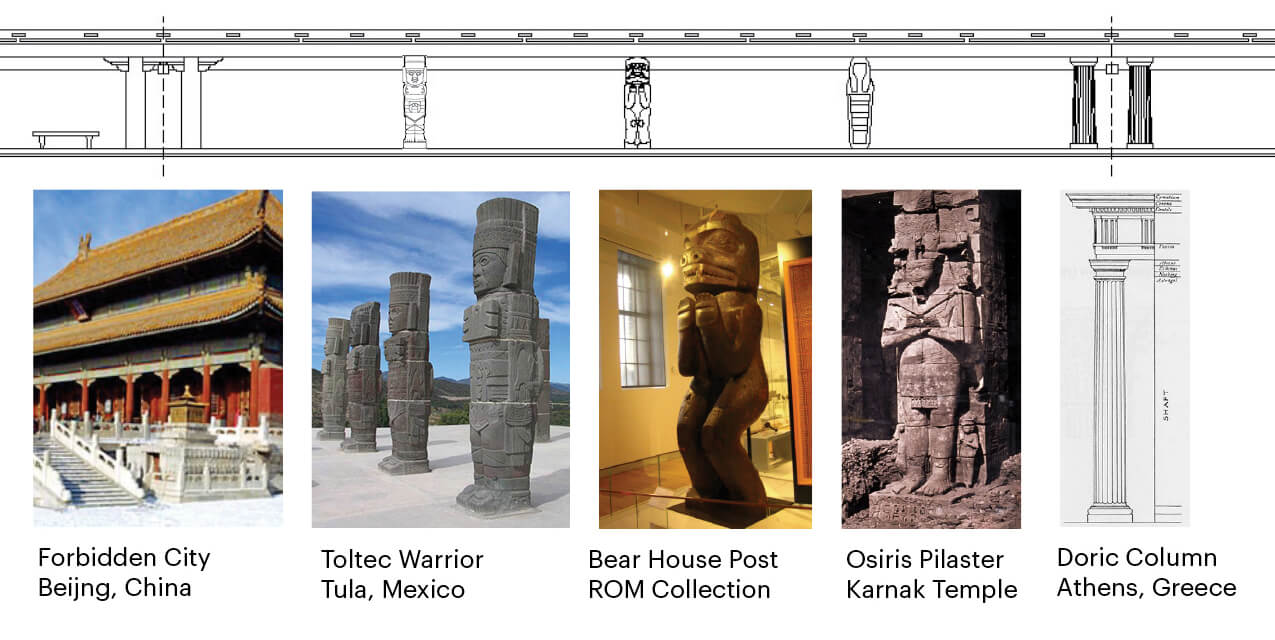

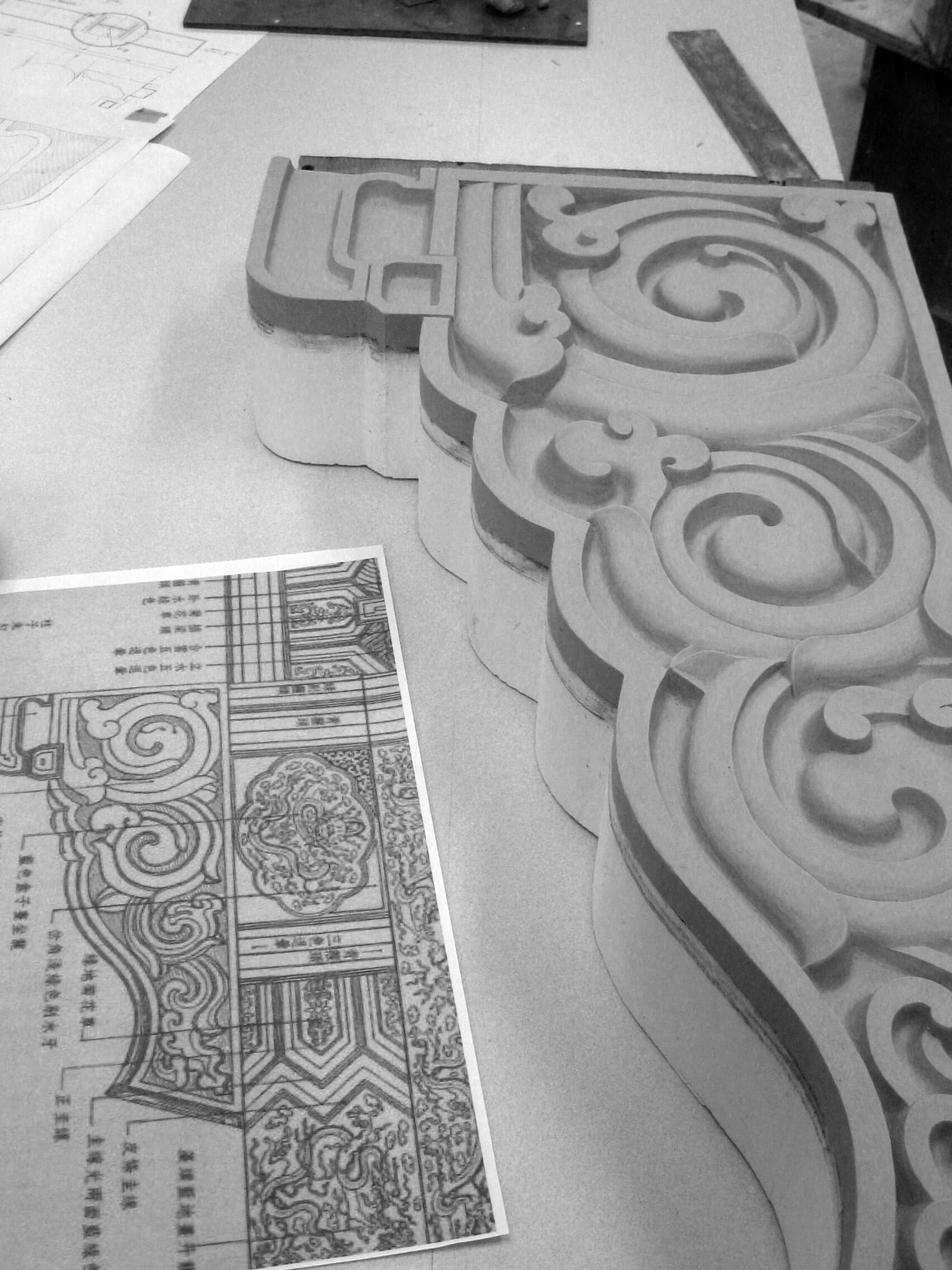

The column designs were the result of months of collaboration between the architects, curators and specialists from the Museums, the fabricator, and individual artists. Diamond Schmitt collaborated with the client to choose the artefacts to be replicated. The team looked at a variety of options, before deciding on artefacts that would have been weight bearing in their original uses.

Specialized curators were brought on board once the artefacts were selected. Diamond Schmitt worked closely with specialized curators Kenneth Lister, Roberta Shaw, Paul Denis, and Sara Irwin from the ROM, and Helen Haines from Trent University to replicate the artefacts as columns.

The fabricator, Design Plaster Mouldings, employed artists to create full-scale carvings based on the artefacts. The architects and museum curators visited the factory regularly giving the artists feedback as to size, shape and proportion – ensuring that the finished columns are representative of the artefacts that inspired them. The extremely durable columns were cast in glass fibre reinforced cement and designed to withstand the normal wear and tear of a subway station.

Museum Station was still operational during construction, with renovation and installation work taking place outside the operating subway hours, between 2am and 8am.

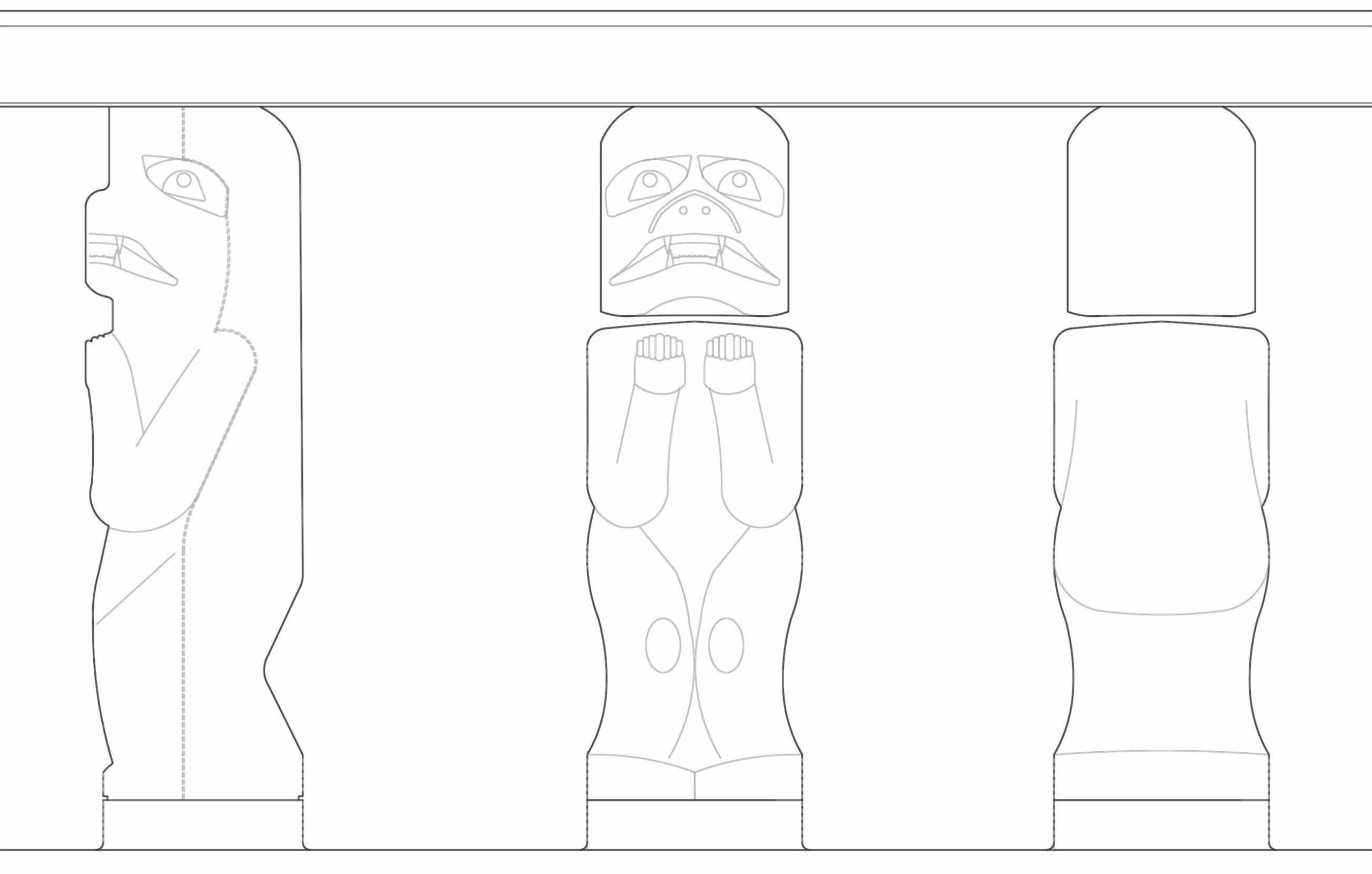

Wuikinuxv Nation Bear House Posts

The Wuikinuxv Nation Bear House Post is modeled after a house post from the Wuikinuxv Nation at Rivers Inlet in British Columbia. The original post supported one end of a home’s massive roof beam. The post was carved from a single cedar log and the marks covering the surface of the post were created by the carver’s adze. The bear is a traditional family crest figure that identified the home’s family and their status.

Acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum after the house had been abandoned and dismantled, the original artifact can be found in the Daphne Cockwell Gallery of Canada: First Peoples.

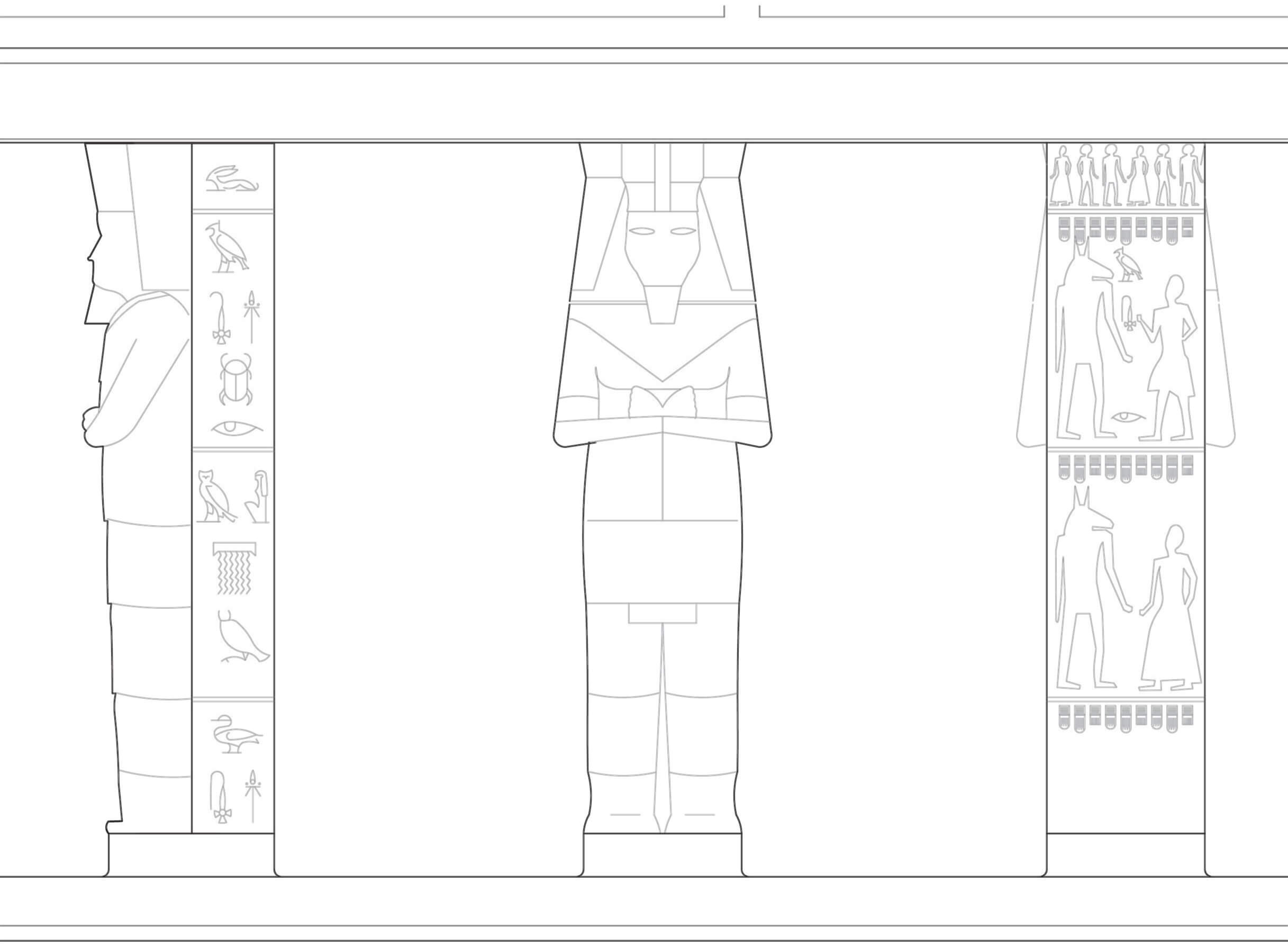

Osiris Columns

The royal monuments of ancient Egypt often featured colossal human figures as supporting columns. In temples dedicated to deceased kings, these rulers were often featured as columns in the form of Osiris, the god of the dead and eternity.

The upper half of the pilaster featuring the royal headdress, the crook and the flail, identifies a king. The wrapped lower half identifies the god Osiris who is typically depicted as a mummy in Egyptian mythology.

The hieroglyphic inscription on the back of the pillar is copied from a relief found in the Egyptian gallery at the Royal Ontario Museum and reads: (The king) offers the best fresh incense to Amun-Ra, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, Lord of the Sky, so that he will give (the king) life, stability, dominion, health and joy like Ra, forever.

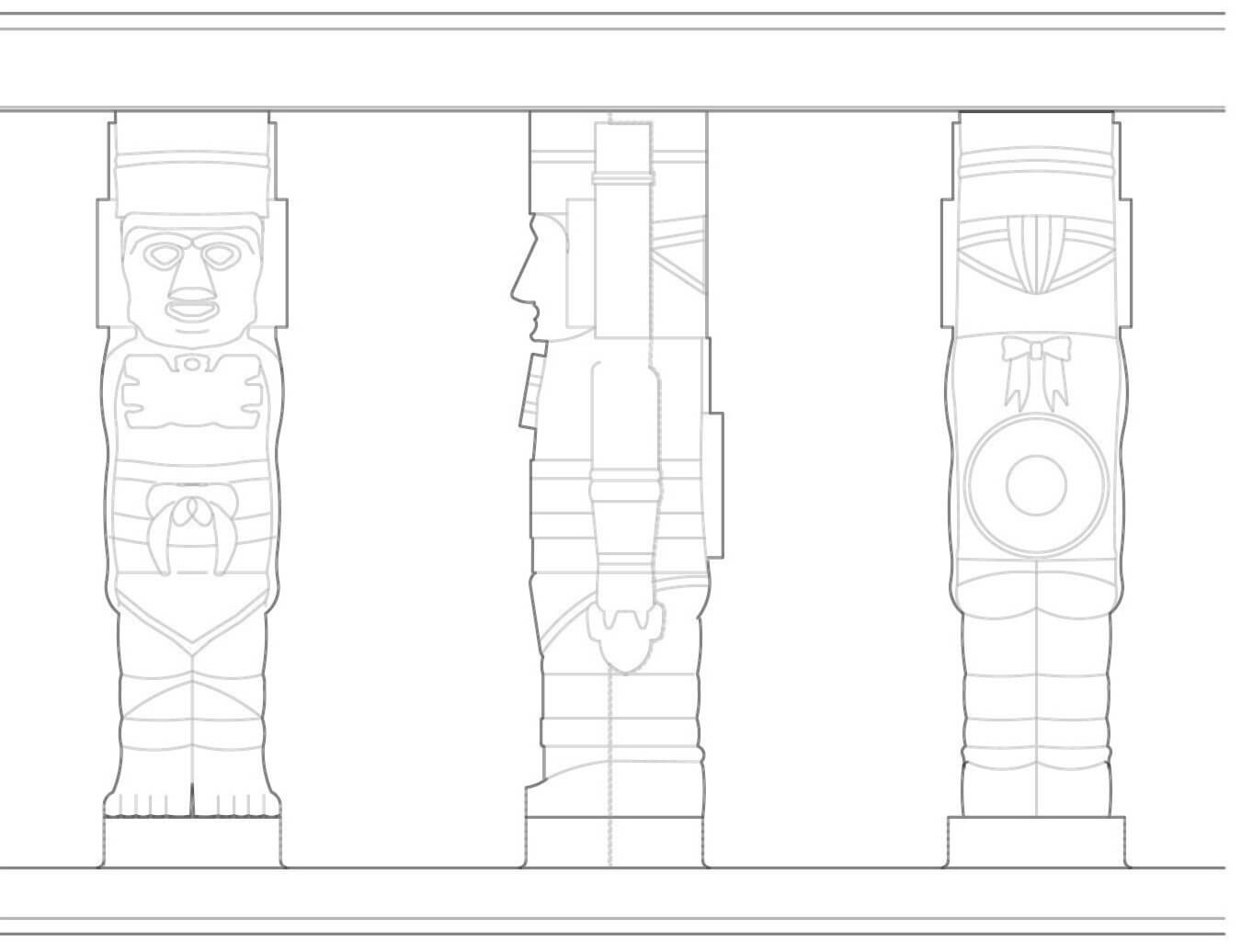

Toltec Warrior Columns

The Toltec Warrior column is a replica of one of four warrior columns located atop a temple in the ancient Toltec capital of Tula, Central Mexico. The Toltecs dominated this area from around 900 to 1150 AD influencing the cultures of the Maya and Aztecs. The figure on the column is believed to represent the warrior-god Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli in the guise of the evening star, Venus, which is often associated with warfare in Mesoamerican cultures.

An example of a Toltec Warrior-like figurine can be found in the Gardiner Ceramic Museum’s Ancient America’s gallery, displayed with other works from the Maya Classic period. The Royal Ontario Museum also has a prestigious research history of Maya Culture in Mesoamerica, including Belize and the South American Andes.

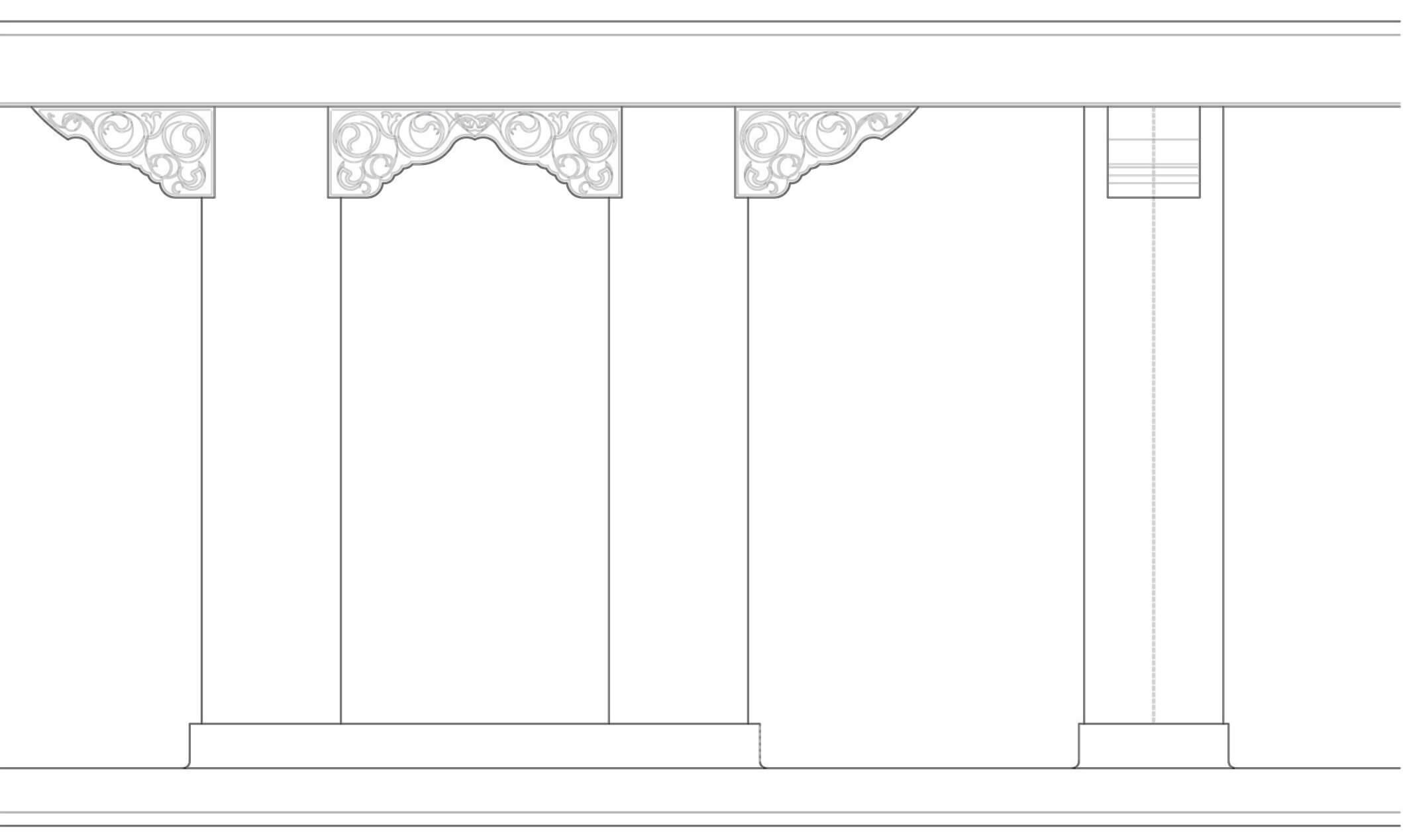

Forbidden City Columns

The design of these columns is based on the columns surrounding the Hall of Perfect Harmony in the Forbidden City, the palace of the Chinese Emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1912). Like most Chinese imperial palace and temple buildings, the columns are painted red, a colour that traditionally represents happiness and good fortune. The roof would be covered with ornamental tiles glazed yellow, a colour only the Emperor was allowed to use.

An example of this type of architecture can be seen in the Gallery of Chinese Architecture at the Royal Ontario Museum, which houses a full-scale reconstruction of a corner of a large palace hall in imperial style of the Qing dynasty.

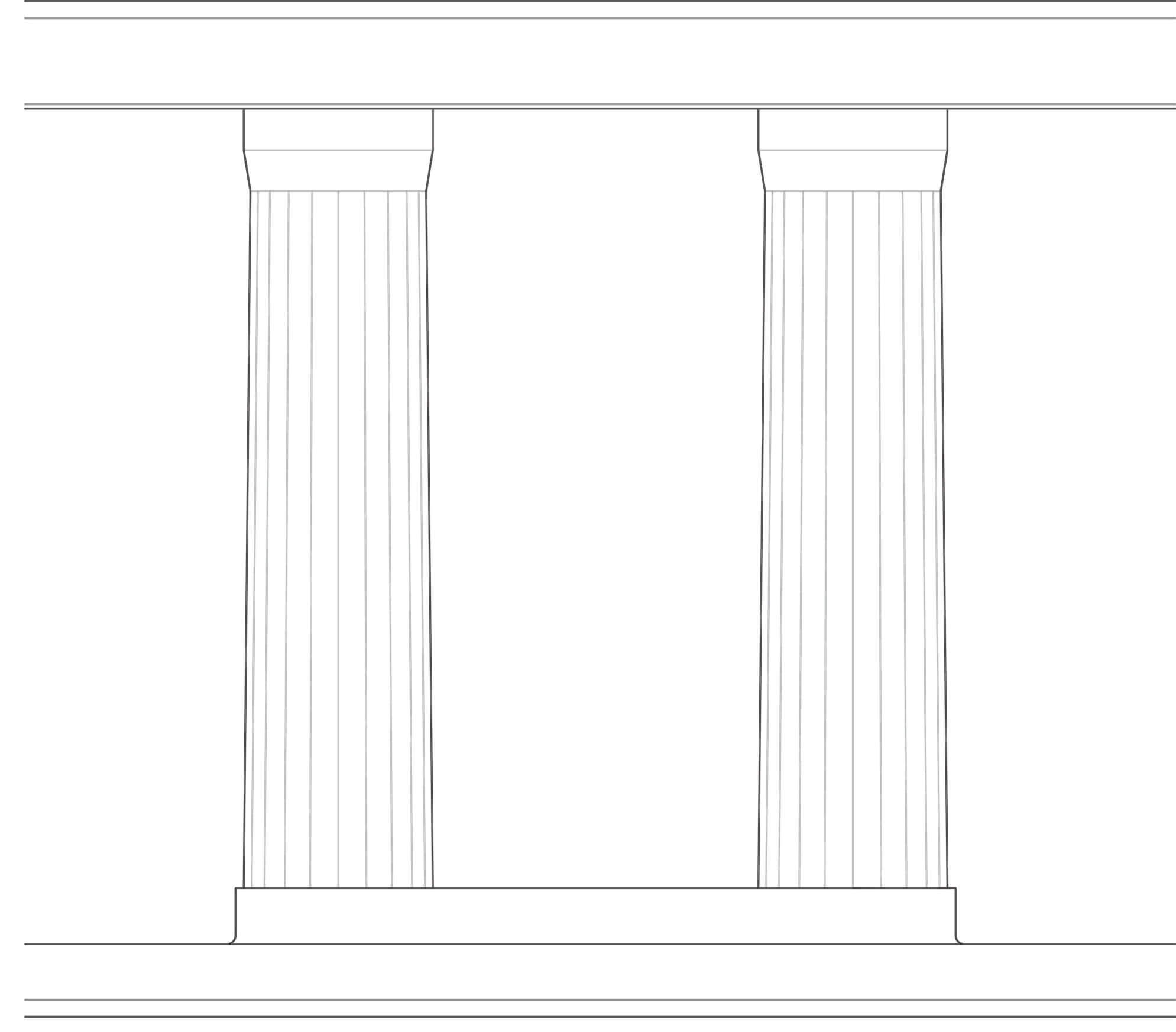

Greek Doric Columns

The fluted white double columns are derived from the Doric columns used in ancient Greek temples. Historically, Doric columns are characterized by gradually tapered shafts that stand directly on the floor or foundation of the temple. The shaft is usually made from a series of stone drums placed one on top of the other with 20 vertical flutes carved around the shaft. The smooth capital at the top of the column flares out to meet the supported beam above.

From the time of its inception in ancient Greece through to mid 20th century, the Doric column has remained an important structural and decorative architectural component. They are used in a vast number of buildings in Europe and North America with the most prominent Toronto example being the columns lining the façade of Union Station.

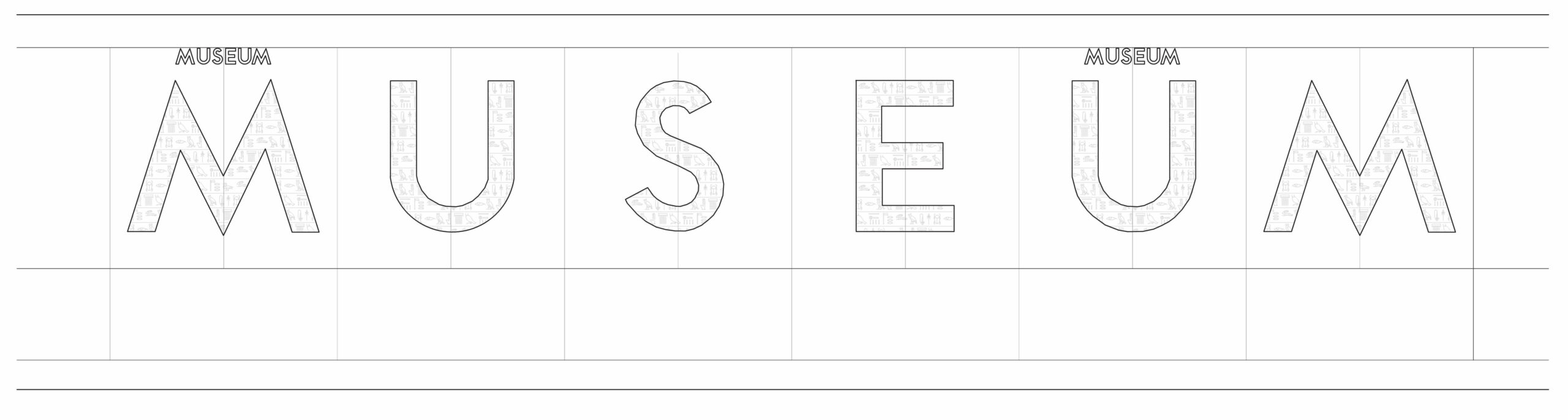

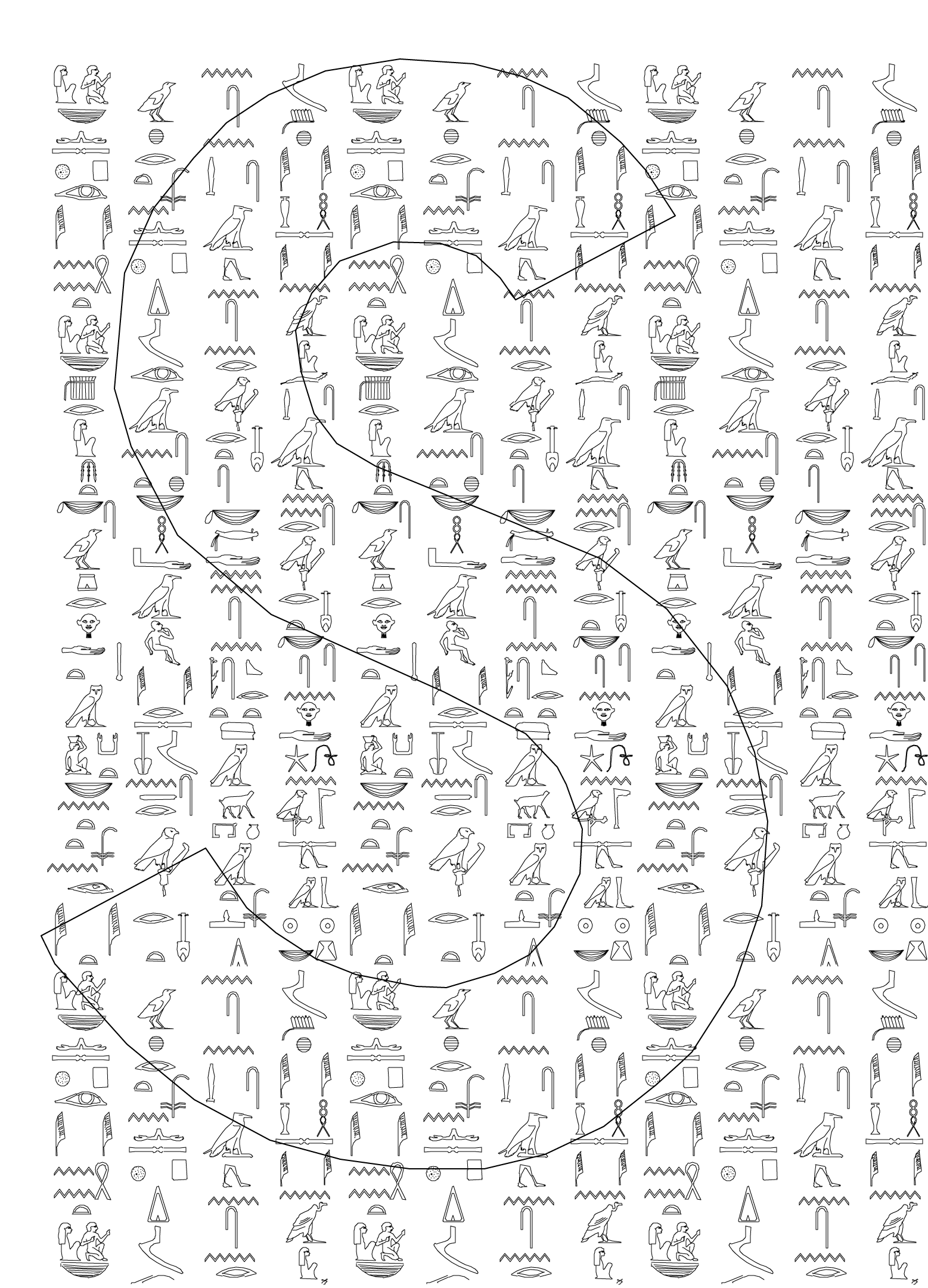

Hieroglyph Track Wall

The design team worked with Ontario Panelization to create the new track walls in the station. The backlit panels were 3mm aluminum plate, with fire rated 1/4″ lexan behind the panels for the Museum letters. The hieroglyphs were CNC machined on the back of the panels.

The inscription contained within the letters on the track wall is from a limestone relief in the tomb of an ancient Egyptian nobleman named Met-jet-jy. Dating to approximately 2300 BC, the original artifact is housed in the Egyptian Gallery at the Royal Ontario Museum.

The inscription reads: “I was loved by my father, honoured and praised by my mother. I gave them a proper burial – by royal decree because I was honoured by the king – so that they could praise the god forever. I was a good son from my childhood until their demise, never causing them anger. Moreover, my opinion was considered in every royal project.”