Creating Culture Spaces for the Future

By Gary McCluskie , Matthew Lella , Sybil Wa

January 30, 2023

The past two years have seen a reckoning for cultural institutions. Alongside the challenges of connecting with audiences while venues were dark during the pandemic, they (and those of us who help create their venues) have faced a long overdue confrontation around equity and inclusivity. This is not only about who these institutions and spaces serve but how they serve, expanding past their roles as cultural programming often perceived as exclusive, to community gatherers that welcome and uplift a multiplicity of voices, traditions, and ideas.

As architects for the performing arts, we approach this challenge from the perspective of space. Our relationship to space has the power to structure and reify our social relationships; it can define who is an insider or outsider, create comfort or alienation, separate or bring people together along cultural lines. While the world’s leading performing arts institutions have long held an iconic place in the skylines, guidebooks, and imaginations of their home cities (not to mention for visitors and aspiring performers from around the globe), they now find themselves asking: who were our facilities originally designed to serve, and how can we reconcile this existing architecture with a more inclusive vision?

Performance venues have tended to reflect the class dynamics, civic aspirations, and aesthetic conventions of the time in which they were created. Even Shakespeare’s Globe, famous for its accessible ‘theatre in the round,’ made distinctions between the standing-room pit for the general public and the plush galleries above that gave nobility premium views.

The proscenium model, which separates the auditorium from the stage with a frame or arch, has characterized the design of European and American theatres and concert halls throughout history. This approach has not only divided audience members by class through disparate experiences between tiers, but also by physically setting performers apart from audiences.

What’s more, through much of the 20th century, the standard classical concert audience was overwhelmingly white and wealthy or middle class; the repertoire was canonical; and the musicians themselves, in professional orchestras across the United States and internationally, were almost exclusively white men—biases that manifest in much midcentury architecture. In contrast, orchestras today are increasingly striving to diversify their ranks and emphasize the music’s social context and relevance, whether performing celebrated historical works or embracing the innovations of contemporary composers.

As organizations look to create a future that breaks boundaries between audiences, genres, styles, and mediums, they need performance spaces that can enable these aspirations. But what does that look like in practice?

When Diamond Schmitt was selected to lead the master plan and design process for David Geffen Hall in 2015, the longstanding home of the New York Philharmonic and an iconic architectural anchor of Lincoln Center’s campus, we became part of a historic trajectory, as the space had already undergone two major renovations since its construction in 1962. But while these renovations addressed some acoustical challenges of the original design, the overarching character of the space remained unchanged—spartan, designed for a homogenous audience, and limited in the sounds and performance formats it could accommodate.

The team was motivated to design a human-centred model encompassing the diversity of the audiences and artists who would use the space in the years to come. Thus began a dialogue with both organizations to determine what their concert hall of the future should be. Through extensive conversations with musicians, staff, and leadership, we arrived at a few key traits: the hall needed to be warm and inviting; it needed to have exceptional acoustics for orchestral music while being flexible enough for new kinds of performance; it needed to honour the history of Lincoln Center’s campus; and it needed to be accessible and inclusive by design. We were inspired by this to create spaces that were less of a manifesto, and more of a poetic interpretation of these priorities through architecture.

The new David Geffen Hall that opened its doors in October 2022 goes beyond acoustical quick fixes to a larger reinvention of purpose. It honours Max Abramovitz’s travertine exterior as a world-class home for classical music while expressing a fresh, contemporary identity, creating a highly flexible and user-driven space that offers an uncompromised and welcoming experience for all. Not only does it meet the social and technical needs of the present, but it anticipates those of the future, ensuring its success and sustainability in the decades to come as both a performing arts venue and a civic hub.

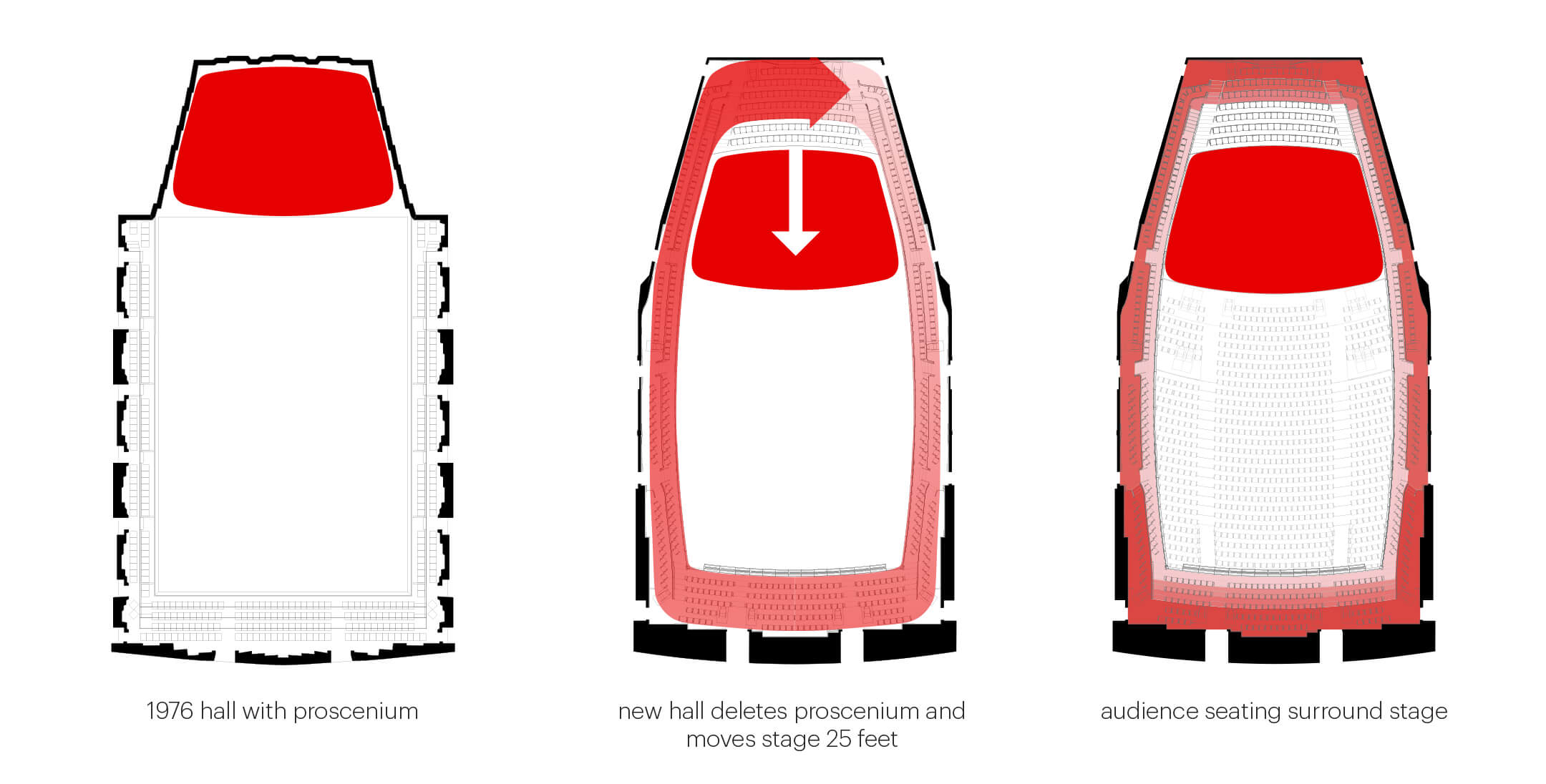

In the hall’s Wu Tsai Theater, we started by eliminating that historic model of a proscenium stage, removing the barrier between audience and performer and bringing everyone into a single room. By reducing the seat count, bringing the stage forward by 25 feet, and wrapping the upper tiers around the stage, the performers are brought closer to the audience while dissolving the tiered hierarchies so often felt in spaces of this caliber. Whether you are sitting in centre orchestra or in the back of the third tier, each audience member will have ideal sightlines and exceptional acoustics while feeling truly together in the space.

We also wanted to ensure that each audience member felt immediately welcomed, which influenced our approach to the materials. The warm, rippled beech wood paneling evokes the interior of a musical instrument, creating an idealized environment for musicians and audiences alike. Architectural choices like these that enhance acoustics also play a role in shaping the hall’s social character, manifested through a “surround-style” layout designed for intimacy. Improving physical accessibility was also a necessity, including an increased number of accessible seats throughout the theatre, additional elevators, wheelchair platform lifts, and bathrooms, and an optimized livestream setup to bring performances to audiences beyond the hall.

In addition to considering audiences, Diamond Schmitt worked closely with the New York Philharmonic to tailor features to the musicians’ feedback, immersing our team into their operational routines and creative processes. Onstage, this informed the precise placement of new motorized stage lifts and custom-tuned acoustic panels. Backstage, significantly expanded amenities anticipate artists’ needs holistically and correct the architectural biases of a space previously configured for a predominantly male orchestra—for example, moving instrument storage that was previously located in changing rooms into its own gender-neutral space. Nursing rooms allow working parents to care for their children, additional bathrooms account for gender equity, and a new suite of practice rooms enables Philharmonic musicians to teach, rehearse, and make the space their own throughout the day.

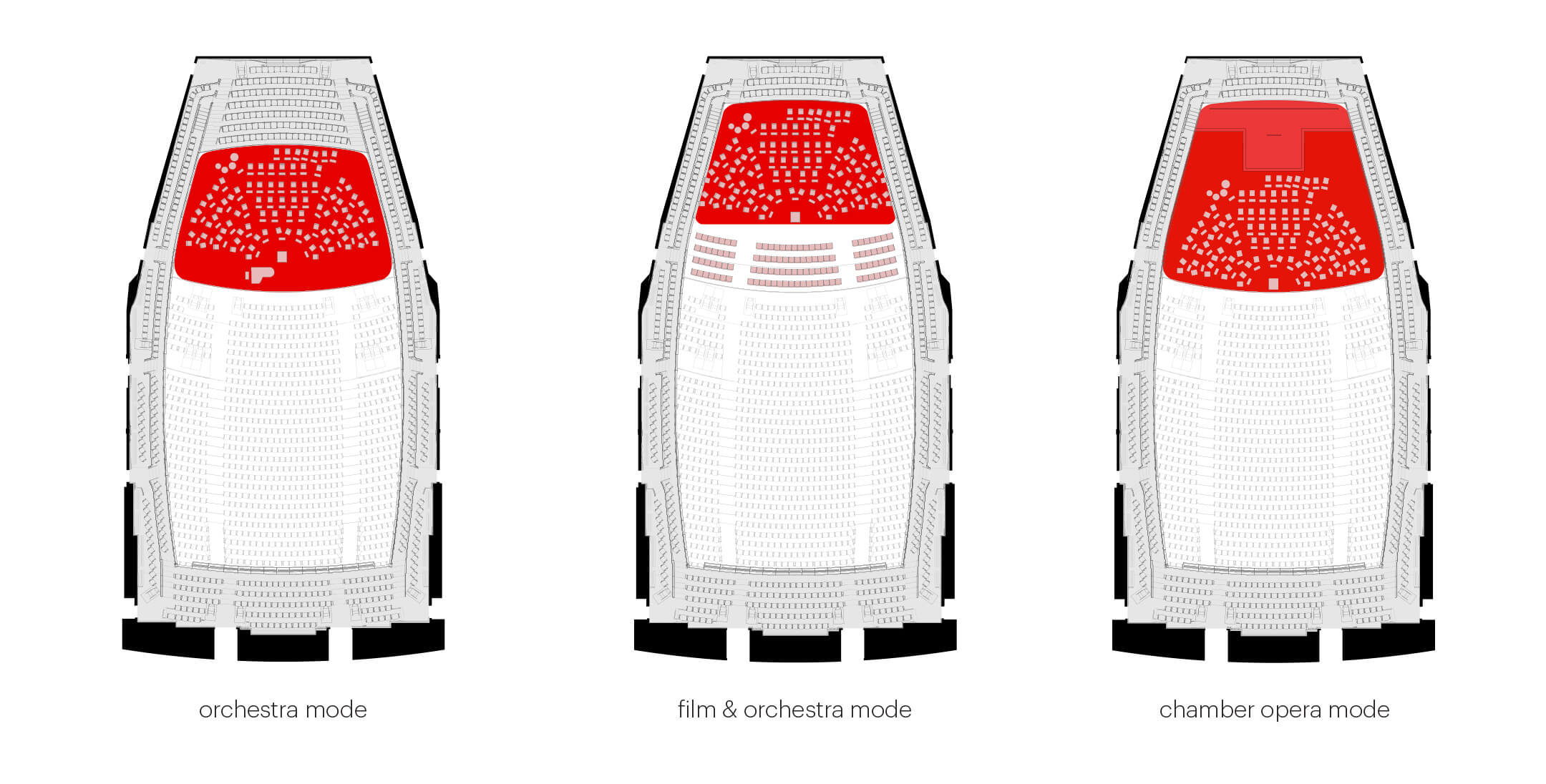

Artists with innovative and unexplored new visions will have a dramatically expanded range of expression as well, with advanced stagecraft, rigging, lighting, and acoustic tuning that can transform between a multitude of configurations for orchestra, solo and small ensemble concerts, film, pop and electronic music, staged operas, and more.

We are pleased that the hall’s new design still resides in that iconic travertine-clad exterior immediately recognizable to Lincoln Center—and it is a useful reminder that looking toward the future does not have to mean erasing our past. Programming and art installations have honoured the history of San Juan Hill, acknowledging the harmful values and decisions that allowed these spaces to come to be, while inaugurating the doubly-expanded lobby and new welcome centre— brought to life by our design partners Tod Williams and Billie Tsien—as spaces that reach out and invite in the community on the plaza and beyond.

Through cultural projects like Geffen, we aim to take steps toward a more inclusive future, break down barriers, and use architecture to enable new possibilities for togetherness, openness, equity and discovery. Flexible and human-centred design allows institutions to evolve with the future, continuously adapting to serve changing audiences and art forms for generations to come.

Photos by: Michael Moran and Chris Lee